Our Story

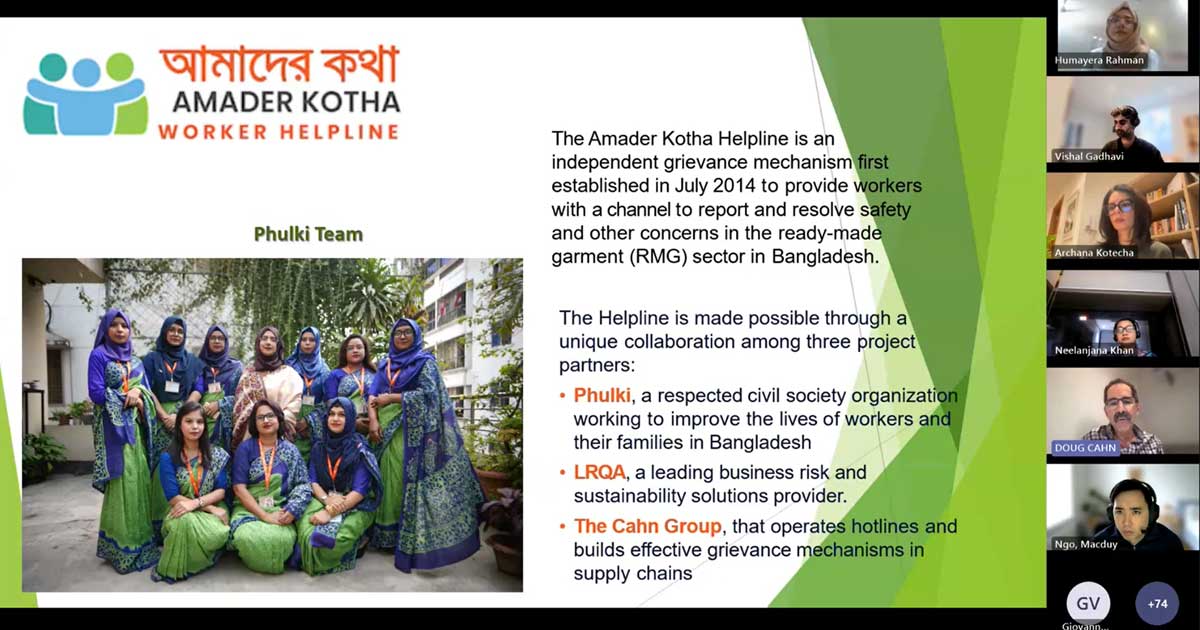

The Amader Kotha Helpline™ was first established in July 2014 to provide workers with a mechanism to report and resolve safety and other concerns in the RMG sector in Bangladesh. The Helpline was initially established as a project of the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety following the Rana Plaza tragedy. In July 2018, the Helpline became an independent initiative available to all garment workers with the support of factories and brands. Amader Kotha is a unique collaboration among three project partners – Clear Voice, a project of The Cahn Group that operates hotlines and builds effective grievance mechanisms in supply chains; Phulki, a respected civil society organization working to improve the lives of workers and their families in Bangladesh; and LRQA, a leading global assurance company. Each partner brings years of experience building innovative, best-in-class labor compliance programs in supply chains. Read More

Awareness

Accessibility

Accountability

Awareness

Our goal is that every worker receives the Helpline card and for all workers to know how to call and what to expect when they do. We do this with in-factory training sessions. We distribute Helpline cards that are sized to fit on lanyards carrying factory ID cards. We provide posters and other visible material for posting in the factories. We give factory managers public address announcements to play periodically and ask for reports on frequency of use. When awareness levels of workers are low, we prioritize the factory for additional training

Accessibility

The Helpline is toll-free nationwide and available during key hours. Helpline officers are trained to be sensitive to labor conditions, to record information accurately and completely and to always follow-up with workers as information about their concern becomes available.

Accountability

Protocols require timely reporting, recording of responses from managers. And validation of reports whenever possible. Workers are always informed about progress on resolving their issue or concern. We use Interactive Voice Response (IVR) surveys to capture the rates of satisfaction of workers and to learn worker attitudes that can improve Helpline operations.

Our Story

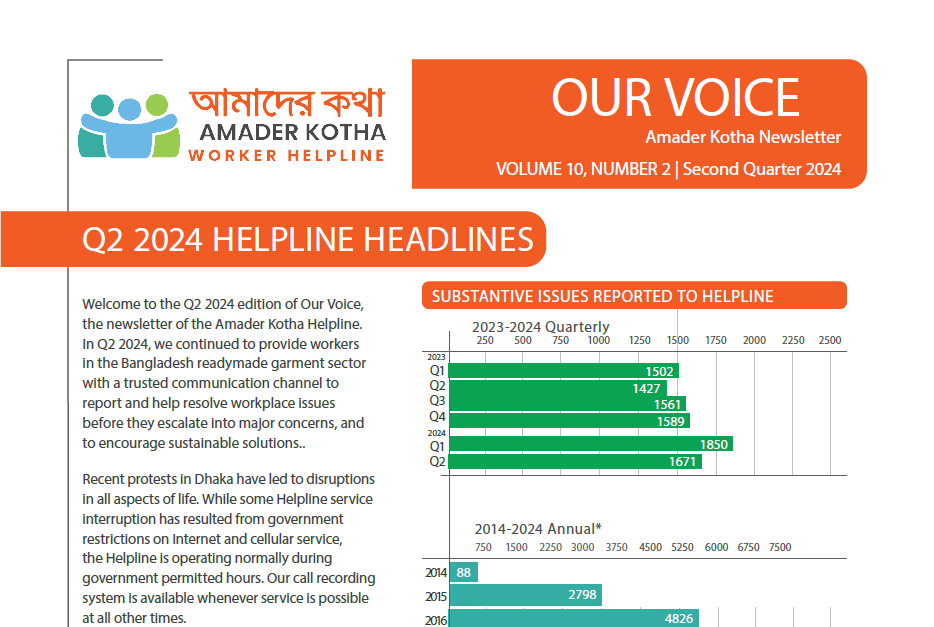

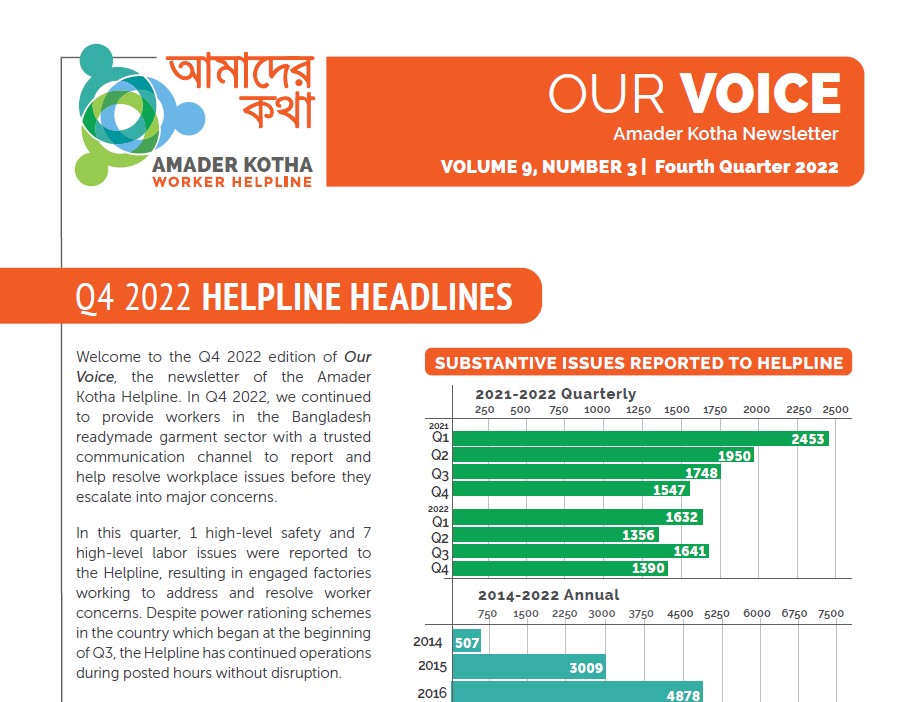

Our numbers speak for themselves

1.5 M Workers

Workers trust the system. We know because they call frequently, they tell their friends about it, they are willing to share their identity, and issues are resolved to their satisfaction.

Issues Reported Monthly

%

Shared Their Name

Factories Calls

Monthly Calls

%

Issues Resolved

Amader Kotha Helpline subscribers (partial list)

HELPLINE SUCCESS STORIES

In 5 years, we have saved lives and protected people and property by giving workers a trusted early warning system.

Fire Danger

Sparks were reported coming from an electrical circuit on the 3rd floor of a factory by one of the factory operators. When workers attempted to ring the fire alarm, it did not work. A similar event occurred a short time later the same morning. After being notified, management allowed workers to leave the building until the cause of the sparks could be resolved and the malfunctioning fire alarm could be fixed. Some days later, calls to workers in the building confirmed that the problems had been resolved

Building Safety

A worker observed cracks in the male bathroom of about 15-20 feet in length between the roof and the joint wall. Most of the required retrofitting and strengthening of the factory’s support structures had already been completed. The worker, Rashid was concerned that the cracks he found posed a risk. The factory was contacted right away and it was determined by experts that the cracks were not dangerous. This news was communicated to all workers in the factory over the public address system.

Construction Integrity

During a factory construction project, a 3rd-floor sewing operator called to report that several vertical beams had been cut and the building was shaking. After a review of the situation by a qualified expert, the factory ceased the construction work and will begin again only when proper precautions for structural integrity are in place.

Fire

At 11:30 a.m. in the morning, fire broke out in the 1st-floor washing division of a factory outside Dhaka. The Helpline received notice almost immediately from Iqbal who was working nearby. “I was unable to find the number for the fire brigade, but I had the Helpline number,” explained Iqbal. “Now we are conducting monthly fire drills in the factory and management is taking fire prevention very seriously.” As it turned out in this case, the fire brigade had already been notified. But the added assurance of being able to reach the Helpline to make sure the fire authorities were on their way provided an extra layer of protection and comfort to Iqbal. No one was hurt and there was no significant damage to the factory.

Wage Payment

A newly hired sewing operator called the Helpline for support in getting the wages due her after she was terminated. She was asked to leave the factory during the probationary period because she failed to meet the production target. When the caller asked for her payment, the supervisor refused.

Prevent problems through better insight

Resources

Amader Kotha at the OECD: How We’re Measuring Real Impact for RMG Workers

Assessing Grievance Mechanism Effectiveness at the OECD Forum At an OECD Forum virtual side session held in February 2026, Amader Kotha Helpline partners joined Primark and The Remedy Project to discuss a critical question facing the global supply chain: How do we know if grievance mechanisms are actually working for the people they are designed to protect? The webinar, titled “Evaluating Effectiveness of Grievance Mechanisms,” provided a deep dive into an independent study commissioned by Primark and facilitated by The Remedy Project with the full cooperation of the Amader Kotha Helpline. The evaluation is based on the UN Guiding Principles (UNGP) and is investigating not only how the Amader Kotha Helpline helps worker voices to be heard, but also leads to genuine remediation. A “Floor, Not a Ceiling” Approach to the UNGP The discussion focused on the rigorous application of the UNGP Principle 31 effectiveness criteria to the Amader Kotha Helpline. This involves a rigorous, four-phase evaluation process—ranging from document reviews and operator interviews to the most critical stage: direct feedback from the complainants themselves and analysis. By conducting independent interviews in Bangla the evaluation team led by The Remedy Project expects to be able to measure whether the remedy […]

Launch of The Amader Kotha Helpline Worker Training Video

We are pleased to announce that the Amader Kotha Helpline in Bangladesh has recently developed a new animated worker training video as a next step in our efforts to support a high level of worker awareness and trust. The video provides workers with detailed information about how to access the Helpline and what to expect when a worker calls to report safety or labor related concerns in the workplace. It serves as an additional tool to complement our printed posters, cards, and stickers as well as our in-person trainings when requested. The video is available in English and Bangla. We encourage you to take the time to watch the video as part of our ongoing efforts to provide information about the Helpline and how it can support safe and decent working conditions in Bangladesh.

Access to remedy: Practical guidance for companies

A guide published by the Ethical Trading Initiative for companies to establish and participate in effective UNGP-informed remedy mechanisms for workers who may be adversely impacted by business operations, products, services or relationships in the entirety of their supply chains

A New Logo for the Amader Kotha Helpline

We are pleased to announce that the Amader Kotha Helpline in Bangladesh has updated its logo. As part of our ongoing commitment to improving the worker experience and promoting workplace rights within the RMG sector, we wanted to refresh our brand identity and give it a more modern and inclusive look. Our new logo features three people arm-in-arm, representing the value and strength of worker voice in Bangladesh. The new logo reflects our belief in the importance of collaboration and community in addressing workplace issues. When designing our new identity, we surveyed workers to gather their feedback on several different designs to understand which design they felt most connected to, while maintaining strong brand recognition to the Helpline. We believe that our new logo will help us better connect with workers and communicate the importance of their voices in the grievance process. We know that workers in Bangladesh often face significant challenges in speaking up about workplace issues, and our goal is to create a safe and supportive environment where they can be heard, have their challenges remediated and their rights protected. At the same time, we recognize that a logo alone is hardly sufficient to create lasting change. We […]

Ensuring fashion supply chain grievance mechanisms are truly effective

The well-intentioned efforts of fashion brands and retailers to put in place grievance mechanisms in their supply chains are missing the mark. Companies should consider sector wide approaches, writes corporate responsibility consultant, Doug Cahn. This article was first published on 4th May 2023 by JustStyle and was republished here with permission. You may find the PDF version here. When John Ruggie, special representative to the UN secretary general for business and human rights, conceptualized the foundational principles for effective grievance mechanisms throughout the supply chain he understood the central role that fashion brands and retailers would play. He called on companies to ensure access to those mechanisms be a part of a company’s commitment to respect rights. When it came to operational-level grievance mechanisms in particular, he understood that a company’s obligations could be administered not only by each company acting alone, but by companies in collaboration with others. This is relevant for global brands today as regulators in Europe and elsewhere require transparent communications that document the impact of brands’ initiatives to protect workers in their supply chains, including their grievance channels. Do grievance mechanisms for fashion supply chain workers work? Leading fashion brands and retailers have invested significant […]